A Gentle Yes

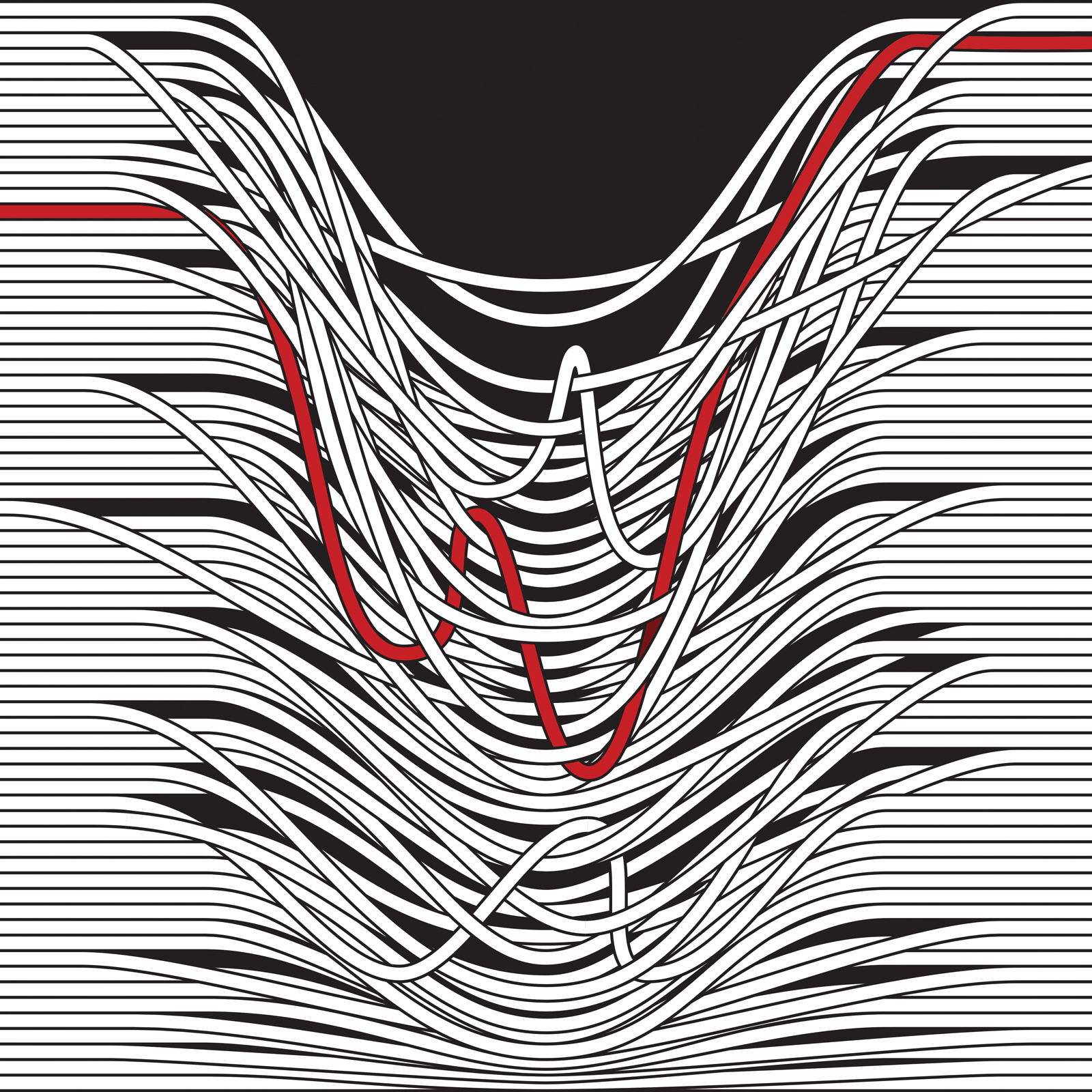

“God is far more interested in my honesty before Him than in my pretense of belief.”Even in my moments of greatest faith, I still carry with me a thread of doubt. I have learned to live with this thread of doubt, to acknowledge it and stop pretending it doesn’t exist.

I used to be afraid of it because I thought if someone pulled its thread, the whole tapestry of my faith would fall apart. But I have learned that denying the thread exists is to make it a monster. Denying that I question whether God can or will or might or should or could do something beautiful or good or right in various situations isn’t honest before God.

God is far more interested in my honesty before Him than in my pretense of belief. God can do something with my doubts and my belief in that is bigger than my doubt itself.

This is how I comfort myself when my faith feels threadbare, or the string of doubt threatens to strangle me. I tell myself, God is not wasting this fear of mine, this lack of belief, this shred of uncertainty. He is at work in it and through it for me, beginning with my honesty that it exists.

I have begun to think of doubt as a type of blindness.

When I was little, we had a blind piano tuner come to our house every year. I don’t remember his name, but he was a rotund man who wore plaid shirts tucked in and a swath of hair swiped across his bald head. Our piano was at the bottom of the stairs and we kids would sit on the steps, hands gripping the spindles, and watch him with something like delight and fear and a little bit of awe all at the same time.

He would sit down, open his case, take out a tuning fork, look up in our direction and hold a finger over his lips to shush us. And then he would tap that fork on his knee until it made the clearest “A” you ever heard. He’d press a key, tap the fork and tighten a string. Press a key, tap the fork and tighten a string. On repeat. Then he’d play a chord, tap the fork and tighten a string. He’d do this for an hour, and we watched the whole thing because we knew what would happen when it was over.

Without fanfare or a word, so quickly that we hardly knew he’d finished, the piano would alight with song. He’d play scales and trills and sonatas and twelve variations on a theme. He was nothing short of magic to us, this man who couldn’t see a single thing tuning that piano and making it sing again.

Years later I wonder if he was as spectacular of a pianist as we thought as kids, or whether it was the anomaly of him that made it all so wonderful. What made him brilliant to us was his disability. The thing about him that made him different was the thing about him that made him spectacular.

Once after he left, I asked one of my parents how he could do it, tune by ear and play by ear like that. They told me when one of your senses is diminished, sometimes the other senses make up for it. Our piano tuner’s pitch was perfect and his ability to play whole pieces by simply hearing them was part of the way his body compensated for the lack of seeing.

This is how I think about doubt in a believer’s life, as a form of blindness. A person who cannot see the world around them doesn’t deny it still exists. They may knock their shin on the same coffee table for months or walk the same predictable street for years. They sense the sun on their face or the shadows or the rain or the wind. They feel the faces of the ones they love and taste and smell the food they eat. It’s all real. Just because they can’t see it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

In the same way, I may believe everything about God and His character and the way He moves in the world and in me, but still not be able to see it exactly the way I wish I could. My full sight of Him is hindered in some way. It doesn’t mean I don’t believe it, it just means I don’t see it. I have to learn to live in this world without denying what is true about me, but also living abundantly within its constructs.

The greatest hindrance to my faith is not my doubt but my fear of saying “Yes” to Him while I still have doubt. Yes, to everything He might do or might not, to the things He does that may surprise me or to the things that are hidden from me or the things I could never imagine.

What if the thing that heals my doubt is a thread of yes woven alongside my threads of doubt?

for further study

Read:

- A Curious Faith by Lore Ferguson Wilbert

- The Ragamuffin Gospel by Brennan Manning

- After Doubt by A.J. Swoboda

- Learning to Walk in the Dark by Barbara Brown Taylor

- When Everything’s on Fire by Brian Zahnd

- How to Survive a Shipwreck by Jonathan Martin

- Help My Unbelief by Barnabas Piper

Listen:

- A Curious Faith: The Dark Way of Doubt playlist on Spotify

- The Place We Find Ourselves

- A Curious Faith: Audio Meditations

Adapted from A Curious Faith: The Questions God Asks, We Ask, and We Wish Someone Would Ask Us, by Lore Ferguson Wilbert

Lore is a writer, thinker, learner and author of the books A Curious Faith and Handle With Care. She writes for She Reads Truth, Christianity Today and more, as well as her own site, Sayable.net. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @lorewilbert. She lives in New York and has a husband named Nate, a puppy named Harper Nelle and too many books to read in one lifetime.